Pointing Out the Dharmakaya

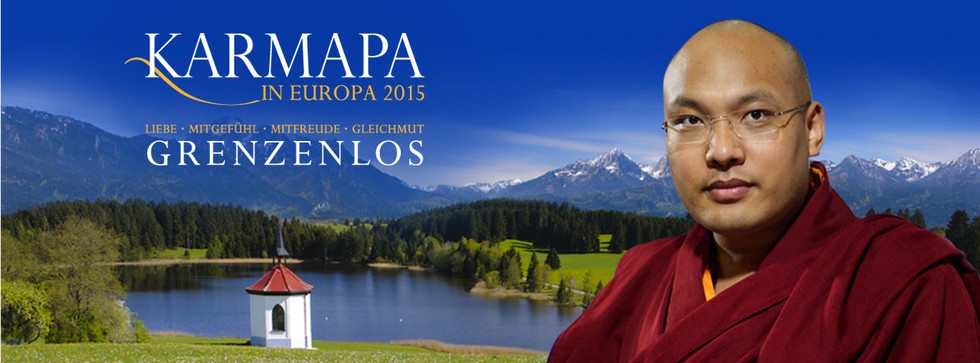

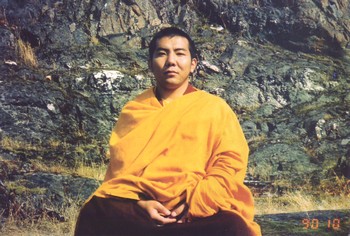

His Eminence the Third Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche,

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge

Instructions based on "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya,"

composed by the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa, Wangchug Dorje

Introduction

I will present teachings based on the text entitled "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya" that was composed by the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa, Wangchug Dorje. It is one of the most important texts on meditation in the Karma Kagyü Tradition. It's called "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya" because it points to the mind. Before I begin, though, I want to remind everyone to give rise to the sincere attitude and pure motivation before receiving the instructions that originated with Buddha Shakyamuni and that have been handed down to us through the masters who have upheld the Oral Transmission Lineage unbroken since that time.

Maybe one isn't attentive of the teachings that are being presented because one isn't concentrated. This is compared to pouring water into a bowl that is turned upside down; it's logical that this bowl cannot contain the water poured into it. In the same way, one may be physically present while the teachings are being imparted, but if one doesn't listen attentively, it's as though one hadn't participated at all. One needs to have a clear and attentive mind and listen carefully to the Lama's words.

The second error one needs to be free of while receiving instructions on the Buddhadharma is being inconsiderate of the meaning of the words by not contemplating the instructions after having received them. For example, one may hear the words but apply no effort in trying to understand the meaning, an attitude likened to a bowl with cracks in the bottom. Any liquid poured into such a bowl automatically leaks out again. In comparison, when one receives the teachings but ignores them, because one fails to contemplate the meaning, they leak out. This is the second error one needs to be free of while receiving the teachings.

The third error that can occur is having disturbing emotions while listening to the teachings. Lacking faith and confidence in the instructions that are being presented pollutes the teachings with one's prevailing mind poison, which are the mental afflictions one stubbornly holds on to. This error is likened to pouring pure water into a bowl that contains poison, in which case the water becomes contaminated. One needs to be free of the third fault while receiving the precious Dharma teachings. I request that you clear your mind of all three faults before commencing and ask you to have pure faith, devotion, and confidence in the teachings and in the teacher who is presenting them. One aspires to understand the instructions correctly so that one will truly be able to help sentient beings become free of the suffering that samsara entails.

Buddha Shakyamuni presented three cycles of teachings that comply with his pupils' propensities and needs. For disciples steeped in daily concerns, the Buddha offered explanations on situations related to relative reality that are experienced in everyday life. He then imparted explanations on ultimate reality for disciples who have a keener capacity to understand the teachings. The teachings I will elaborate here belong to the highest cycle of the Buddha's instructions - Mahamudra. They deal with the subtle and profound truth of reality that pupils with superior qualities can understand.

During the third and last cycle of teachings, Lord Buddha showed the Buddha nature that abides within every sentient being without exception. All instructions on the Buddha nature belong to the third cycle of teachings that the Buddha presented. The Buddha nature is everyone's true nature. It isn't necessary to fabricate or create the true nature as something different than what always and already abides within every sentient being since beginningless time. One's Buddha nature is momentarily obscured, though, which doesn't mean that it is polluted, rather it's concealed by one's mental and emotional defilements. Buddhahood doesn't mean one becomes someone else and different than one already is, rather one realizes one's true mind, in its entire abundance, when one accomplishes Buddhahood. A Buddha has realized his mind's true nature; an ordinary living being hasn't.

As mentioned, the Mahamudra instructions belong to the third cycle of teachings. The Karma Kagyü Tradition is deeply linked with Mahamudra. In the "Samadhirajasutra" and in the "Lankavatarasutra," the Buddha prophesied the coming of a doctor who would perfectly uphold and transmit the Mahamudra instructions. This doctor was Lhaje Gampopa. He founded the Karma Kagyü Lineage, and so the Kagyü Tradition is extraordinary.

The transmission of Mahamudra does not take place through an intellectual understanding of Buddhist literature. Mahamudra is an oral transmission of the meditation instructions that have been handed down through the Lineage from a Lama to his disciples successively and is based on realization of the instructions. A transmission presupposes realization on the part of a Lama, who is able to transmit the blessings of the Lineage, without any mistakes. This is why the Mahamudra Lineage is extremely pure and beneficial - transmission is based on realization. All meditation instructions are profound and are not a mere collection of information.

The Mahamudra Transmission Lineage of meditation instructions is upheld in all Karma Kagyü Schools, which consists of the four major and eight smaller schools. His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa is Head of the Karma Kamtsang Tradition, the school we all follow. The three main texts studied in this tradition were written by the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa, Wangchug Dorje; they are precise descriptions of Mahamudra. He wrote an elaborate, a condensed, and a short version. The long text is called "The Ocean of the Definitive Meaning," the middle-length one is "Dispelling the Darkness of Ignorance," and the shortest is "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya." I will speak about the third text, which consists of eighteen block prints in Tibetan and is a condensed elucidation of the first two.

The Mahamudra path is called the path to liberation. If you are able to practice and when you realize the Mahamudra instructions that you are receiving, you will have achieved liberation. One must be a proper vessel, though, i.e., one needs to be a qualified disciple who is capable of receiving these profound instructions without distorting them. Such a qualified disciple needs the favorable acquirements and must uphold a pure relationship with his or her Lama. When a qualified disciple meets his or her Root Lama, he or she can achieve instantaneous enlightenment and realize the pure state of Vajradhara, Dorje Chang in Tibetan. This is only possible because Mahamudra has the sublime power to instantaneously dispel all mental obscurations that impede realization.

A disciple experiences liberation by means of many different methods and in reliance upon the personal bond he or she has with the Root Lama, who in turn needs to be an authentic and qualified Guru. A Root Lama can point to the nature of the mind by using a symbolical word or gesture.

"Pointing Out the Dharmakaya" is divided into three chapters. The first chapter explains the preliminary practices and is divided into the section on the four general and four special preliminaries; the second chapter teaches the practices of calm abiding and special insight meditation; and the last chapter elucidates enhancing the practice and dispelling hindrances.

I again wish to remind everyone to generate and maintain the pure motivation of Bodhichitta while I continue so that you can fully appreciate the meaning of these profound instructions.

I. THE PRELIMINARIES

The General Preliminaries

The general preliminary practices are the four contemplations that inspire students to turn their mind towards the Dharma. One needs to know that all sentient beings who have ever lived and who live now have the Buddha nature but have failed to recognize it because it is concealed by their obscuring defilements. For one's Buddha nature to manifest, it's necessary to eliminate the main obscuration, which is ignorance of the way things are and they way things appear.

As it is, one discriminates between an apprehending subject and apprehended objects when one perceives things and as a result reacts to one's apprehensions dualistically, which means to say that one allows a disturbing and disruptive emotion to determine one's reactions and behavior. Activities carried out by means of one's body, speech, and mind become habitual patterns that drive one to experience conditioned existence the way one does, and therefore one is deluded. While deluded, one's habits are impulses that drive one to apprehend appearances and experiences the way one does, and one's habits move one to react to one's apprehensions and to repeat one's faults that have led one to experience injury and pain in samsara up and until now. In truth, every living being's mind is by nature pure. The habitual imprints conceal one's pure nature and thus, deluded by them, one wanders from one state of frustration and pain to the other, driven by one's habits and therefore without control, i.e., one remains trapped in samsara due to one's own delusiveness. It's necessary to reverse and eliminate one's habits that determine one's life so strongly. Why does one need to do this?

When one realizes the true and pure nature of one's mind, one is free; as long as one doesn't, one continues one's journey from one unsatisfactory experience to the next. One fails to realize one's true and pure nature because one's habits are extremely strong. They are very subtle and cannot be recognized that easily, otherwise they could be overcome easily. One needs to develop positive and benevolent habits that reverse and replace the negative ones that one has. At an advanced stage of practice, one experiences freedom from good and bad habits, so practice doesn't mean one throws bad habits out and only then one is free to work on acquiring good ones. That's not the meaning.

One begins the journey on the path to refinement by being aware of the qualities each and every action one carries out engenders. One doesn't follow a strict code of discipline, rather one earnestly gives up clinging to cyclic existence by renouncing it. One contemplates the meaningless propositions that "conditioned existence," samsara, offers and, having realized the futility of samsara, renounces any further involvement with it.

One is extremely attached to one's body, to one's relatives and friends, to the environment one lives in, and so forth. Since one has an extremely strong feeling of self-importance, it's necessary to learn to overcome the idea one has of oneself and the world by contemplating the disadvantages of samsara. Should one succeed in giving up futile pursuits, one would see that the suffering one experiences is small in comparison to the pain that samsara as a whole entails. But, first one needs to know about the worthlessness of samsara and realize that it only consists of suffering and pain. Acknowledging that it's possible to become free of the obscured way in which one perceives reality, one realizes that one's own delusiveness has kept one bound in samsara since time that is without a beginning. Now, samsara doesn't disappear through wishful thinking. It's necessary to contemplate the inadequacies of conditioned existence in order to renounce it fully. Having renounced samsara, one can engage in Dharma practices correctly so that one becomes free of suffering.

At this time, one clings to all concrete and abstract appearances. In order to overcome clinging to one's deceptive mode of apprehension, one contemplates the four preliminaries. These contemplations move one to turn one's attention away from deceptive attachment to samsara and towards leading a meaningful life. The first two contemplations concern a precious human birth and impermanence.

In order to engage in the practices of the Buddhadharma correctly, which eventually leads to freedom from bondage, one needs favorable conditions. The favorable cause to attain freedom from delusiveness and manifestation of abundant qualities of worth is (1) the Buddha nature that every sentient being has; (2) the basis is the precious human birth; (3) the influential cause are spiritual friends and our Root Lama; and (4) the methods to attain Buddhahood are his instructions.

1) Contemplation of the Difficulty of Finding a Precious Human Birth

In order to contemplate the favorable situation of having attained a precious human birth, one needs to know about the six realms of samsaric existence. Within the six realms, a human birth enables one to experience happiness, fortune, and success. One knows that the human realm and also the gods' realm are pleasant states of existence, but they eventually change into the suffering of loss and are therefore not ultimate. The only true and lasting happiness one can experience is that of Buddhahood, which never changes and never ends. The best working basis to attain Buddhahood among the six states of cyclic existence is that of a human being. Why?

Our world is called Zambuling in Tibetan, Jambudvipa in Sanskrit. It's very special because it has been blessed by all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in the past as well as in the present. It is a world in which karma ripens very fast; this is not the case in other world systems, in which the results of one's actions ripen slowly. The law of "cause and effect," karma, operates very fast in Jambudvipa, therefore karma is more evident here than anywhere else. In Jambudvipa, one can easily experience and realize the results of one's positive and negative karma, "actions." Without any difficulties, inhabitants of Jambudvipa experience and can know the infallible law of cause and effect, which is a major topic of study in Buddhism and is paramount to achieving Buddhahood. So that's why it's very special to attain a human birth in this world.

But, being born as a human being is not enough to achieve Buddhahood, since there are ordinary and precious human existences. A precious human birth is attained in dependence upon the accumulation of merit. An ordinary and simple human life doesn't lead to Buddhahood, since the circumstances and conditions to receive the teachings must be present and must be practiced. One needs a precious human life in order to attain Buddhahood. What does this mean? A precious human birth means being endowed with the ten favorable acquirements and being free of the eight unfavorable conditions. Only then is it possible to receive and practice the instructions that Lord Buddha presented and to attain fruition. For example, having faulty sense organs hinders one from understanding and practicing the teachings correctly.

Furthermore, a precious human birth means having the influential cause, our Lama, who possesses all qualities of an authentic master and who transmits the instructions and methods of practice to us so that we are able to practice and attain the result. A human body alone does not enable attainment of Buddhahood, rather one needs to have accumulated very good karma, which makes it possible for one to meet one's Lama and to receive the instructions from him. In fact, it's extremely difficult to accumulate all required conditions to attain Buddhahood, which, as mentioned, are attaining a precious human birth with all faculties intact, meeting an authentic Lama, and receiving instructions from him. One needs all factors in order to achieve enlightenment, and therefore one needs very good karma. Should one have all favorable conditions, one will have attained what is called a precious human life, which is the working basis to achieve the ultimate result.

We see so many human beings who are born and pass away. Furthermore, it seems so easy to be born as a human being because we see that there are so many people in the world. The texts teach us differently, though. We read that a precious human birth is very rare, the reason we should not waste it with meaningless activities and pursuits.

Every sentient being wishes to experience happiness and does not want to experience pain. Animals, for example, are said to be dull-witted, because they can't speak or reason, but they too want to be happy and shun pain. There is no doubt that every living being wants to be happy, but they don't really know how to go about to achieve it. Sentient beings run after any chance they think they have to experience happiness and do everything possible to avoid pain, however, in the process they only create more suffering for themselves and others. Some people attain a certain degree of happiness but fail to keep it for a longer period of time. Others find the right means to attain happiness but do not have enough positive karma to experience immediate results. Others achieve happiness but lose it very fast due to unfavorable circumstances. Somebody who has a precious human birth has all favorable conditions. Contemplating that one has a precious life is indispensable if one hopes to fully appreciate one's situation and to persevere in practice. If one has reflected and appreciates having a precious human life, one won't postpone practicing the Buddha's teachings.

We all know what suffering is and experience it again and again. Whether one manages to become free of suffering depends upon one's karma. Simply knowing that negative actions lead to negative results and positive actions bring positive results is not sufficient.

One must win certainty of the law of karma - one must have unwavering understanding of the infallible workings of cause and effect. Then one will strive to make best use of one's life. Even if one has all favorable conditions that define a precious human birth but doesn't practice the Dharma, one will only waste one's most good conditions. Therefore, it's very important to contemplate the teachings about one's precious human life earnestly and sincerely.

This was the first of the three traditional ways to present the teachings on acknowledging one's precious human life. A definition is given and the difficulties of attaining it are discussed, called the explanation by means of the cause. The second traditional way of presenting the teachings on the unique occasion of having attained a precious human birth is referred to as by number. By looking at the number of sentient beings in the world, one sees that there are less humans in comparison to the vast number of animals and insects in the world. One sees that rebirth in Jambudvipa as a human being with all favorable conditions is truly very rare in comparison to the many animals and tiny insects that are born and live here. This, too, is evidence that a precious human existence is very special and rare.

The third traditional way of presenting the teachings on this subject is through similes offered in the texts. One metaphor speaks of a smooth and dry wall without any dents, cracks, or holes. If one threw a hard pea at the wall, it would bounce off like a ball. It is said that it's far more likely that the hard pea will stick to the wall than that it's likely to attain a precious human birth. A second simile speaks of a turtle living at the bottom of the ocean. A yoke with a hole in the middle tosses about on the ocean's surface. It's said to be more likely that the turtle will push its head through the hole in the yoke when it rises to the surface of the ocean every one hundred years than to attain a precious human birth.

Let us now contemplate how hard it is to attain a precious human birth by reflecting the positive merit we have accumulated throughout thousands of lifetimes. We haven't achieved a precious human life by chance or by decision, rather only through tremendous effort we aren't aware of and cannot recall. Some people do not appreciate the value of their life, complain about slightest suffering they experience, even commit suicide, and the like. They just do not understand how hard it is to attain a human life. If they realized the great efforts and hardships that they themselves went through in their many past lives to attain a human life that offers many possibilities to mature spiritually, they wouldn't destroy it.

2) Contemplation of Impermanence & Death

The second contemplation that moves one to turn one's mind away from samsara and towards Dharma is the topic of impermanence and death.

One clings to an apprehending self as an "I," to apprehended objects as "others," and thinks both truly exist of their own accord. It's only due to belief in a self that one creates the idea that things other than the self truly exist as distinct and different. One apprehends objects and either believes in their existence or denies their existence, i.e., one either believes things exist permanently or one denies they exist at all - eternalistic and nihilistic views. This only happens as long as one hasn't realized the true nature of reality. Ultimately, all things are devoid or empty of inherent existence. Since one doesn't realize the ultimate truth, one thinks that the empty nature of all things annihilates reality and, as a result, one falls into the extreme view of nihilism. On the other hand, one might find oneself only acknowledging relative reality and thus one falls into the extreme view of eternalism. Both erroneous modes of apprehension cause one to either believe that things are permanent or of no value at all. One lives one's life in dependence upon one's belief and ignores the continuous change that takes place in conditioned existence.

Impermanence occurs due to the fact that various causes and conditions come together and create phenomena, i.e., all phenomena within and without are compounded when conditions prevail. No phenomenon is a unique entity. Furthermore, whatever is compounded eventually ceases or is destroyed. The truth of impermanence refers to the relative world. The Madhyamika philosophy offers material which enables one to investigate this topic extensively and proves in great detail that all relative existents arise in dependence upon other things, which also rise in dependence upon other things, and so on. One only apprehends relative things in relation to other things. For example, an object is only considered "long" in relation to something else that seems "short." One can only define "high" in comparison to "low." One cannot perceive black without white, and so forth. These are simple examples of interdependence. While failing to realize the truth of interdependence, one assumes that things truly exist through, of, and by themselves, i.e., one assumes that all things are substantial entities and are permanent, consequently leading one's life in reliance upon such ideas. One bases one's life upon one's notion of permanence and believes that what is here today will be here tomorrow. There's no doubt that someone deluded about the truth of reality will suffer when impermanence dawns. However, should one realize the impermanent nature of all things, one would not suffer, would not be disappointment when things inevitably change and cease, rather one would see the situation wakefully aware.

Death is contemplated to realize impermanence. One thinks about the many people one knew who have died. The death of somebody one feels close to or who one doesn't feel close to is heartrending. Often someone's death moves one to reflect that one will die too, but usually one brushes the thought aside real fast or forgets and acts as though one will live forever. And so, one makes plans for a far-reaching future as if one will never die. But, all things are impermanent, change, and cease. One will continue privileging those persons one considers one's friends and fighting against those persons one considers one's enemies as long as one hasn't renounced samsara. Prejudice becomes meaningless in the light of the realization of the transitory nature of all things. Should one realize the truth of impermanence, one would renounce and stop clinging to meaningless things, as though they are permanent and don't end.

This has been a short instruction on impermanence. One needs to integrate these teachings with one's understanding of having attained a precious human birth by contemplating that all wealth and fame one tediously worked hard for will be of no use when one dies - one will have to part from everything then. The only help one can experience at death is one's practice of the Dharma, the reason one needs a precious human birth and should make best use of one's life.

3) Contemplation of Karma

In order to practice Lord Buddha's teachings correctly, one needs to acknowledge the truth of karma. All ordinary beings die due to karma and take karma along. Only a Buddha passes into Parinirvana without any karma.

The body is left behind at death and the mind, accompanied by the habitual patterns accumulated during life and stored in the mind, continues its journey through Bardo, the intermediate state after death. In fact, karma and one's habitual tendencies determine one's future birth. One has no control over one's karma after one has died. Wishes cannot come true then because karma is infallible. Therefore, one needs to renounce futile pursuits and accumulate as much positive karma as one can during life. How does one do this? One should watch one's mind at all times and differentiate between wholesome and unwholesome intentions and actions.

I wish to stress that one needs to carefully watch one's mind and be aware of one's intentions. One should know that non-virtuous behavior arises on account of one's disturbing emotions, the main mind poisons being ignorance, attachment, and aversion, the later bringing on anger, which is the most powerful and dominant mind poison. In the "Bodhicharyavatara," Shantideva wrote that a moment of anger destroys the merit of positive karma accumulated over thousands of aeons. Anger not only destroys one's merit but also harms others. Therefore, one should be very attentive, watch one's mind, and be aware of one's intentions.

If one lives one's life in anger, for instance, one will be reborn in one of the hell realms. Should one let miserliness and greed rule one's life, one will be reborn in the hungry ghost realm. Should one leave one's mind in ignorance, one will be reborn in the animal realm. All experiences are based upon the workings of karma, the unerring law of cause and effect.

Other mind poisons (pride, jealously, etc.) evolve out of the three main ones, which are ignorance, attachment, and aversion. One must watch one's mind and not be influenced by the emotions that one has. As long as one doesn't watch one's mind and isn't attentive of one's thoughts, one will rarely engage in one or any of the ten virtuous actions and will hardly refrain from committing one or all of the ten non-virtuous actions. The ten virtuous actions are (1) not to take life, (2) not to take what is not given, (3) not to engage in sexual misconduct, (4) not to deceive, (5) not to slander others, (6) to avoid harsh talk, (7) to avoid idle chatter, (8) not to have greedy thoughts, (9) not to be malicious, and (10) to avoid having wrong views. The ten non-virtuous actions are their opposite, e.g., killing, lying, etc.

Without having gained conviction in the law of cause and effect, all one's Dharma activities will be in vain. Living a meaningful life is based upon a correct appreciation of karma. I want to ask everyone to reflect each day after it has passed and to check if it was possible to do good or not.

4) Contemplation of Samsara

The last topic that moves one to turn one's mind towards the Dharma is contemplating "the inadequacies of conditioned existence," samsara, which is also associated with karma, since all one's experiences are caused by one's own actions. If one remains ignorant, one will continue experiencing cyclic existence with all its inadequacies from one life to the next. If one realizes the nature of one's mind, then samsara ends.

Each realm of samsara entails different kinds of suffering, particularly the first suffering of change. Any happiness experienced in samsara is transient, too, since it eventually changes into the suffering of loss. Every living being wants to be happy and many people pray to be born as a god, but gods also die in that they fall from the heavenly realm when their positive karma is spent. Being a god, it can see the realm of its doom and consequently experiences pangs of frustration, so it's not advisable to wish to become a god. The demi-gods, on the other hand, are filled to the rim with jealousy, continually fight, and thus accumulate much negative karma. The human realm is mainly that of attachment and desire, but human beings experience the suffering of birth, sickness, old age, and death. Animals experience mental dullness and are only interested in killing and eating. Hungry ghosts experience much hunger and thirst due to having been overly miserly in their past life, which drives them to be greedy. The hell realms are experienced as a result of anger. There are eighteen hells in all, one more horrific than the other and of very long duration. We see that suffering in the six realms of samsara is limitless. The pain we experience as human beings is small in comparison to that experienced by beings living in the other lower realms.

The source of all suffering in the six realms of cyclic existence is the inability to realize non-duality, i.e., the inability to have an unimpaired mind that does not divide into subject and object. We therefore need to establish a mind of equanimity. We need to abandon clinging to a subject and objects in order to achieve the ultimate and changeless state of lasting happiness, which is Buddhahood.

Summary

The purpose of contemplating the four general preliminaries is to have a one-pointed mind that is not distracted by and doesn't succumb to worldly aims. If one hopes to engage in Mahamudra meditation, one needs to have renounced samsara completely and to have won faith and confidence in the Buddhadharma. True faith and confidence in the Dharma presuppose that one has understood quite well that cyclic existence is meaningless. This is why one prays to one's Lama and the Lineage Lamas for their blessings, to help one realize, without a doubt, that renunciation is the basis for correct meditation practice. One needs to switch one's attention from samsara and futile concerns to a pure aim, which is to attain Buddhahood. One does this with stable and concentrated attention.

Should one still be fascinated with worldly things, one would be very distracted and one's meditation would then be faulty. This is why it's very important to contemplate the transient nature of all things. Perfecting this practice inspires one to practice the Dharma with strong determination and perseverance. One trusts that one can tread the path and progress through all stages of practice, until one has attained Buddhahood, and one knows that this is only possible after having renounced samsara completely. This is why I wish to underline the importance of the preliminary contemplations. Perfect understanding of the preliminaries determines whether one's practice will be effective and beneficial.

If one knows that samsara is meaningless, one will be ready to receive the instructions on how to transcend it. The texts state that the milk of a snow lioness is precious ambrosia. If it's poured into a wooden bowl, the bowl will whither away. If it's poured into a golden vessel, it can be contained and will not change. This illustrates the importance of becoming a fit vessel to receive the sacred instructions, by having become free of attachment and clinging to duality, which is the source of samsara.

Of course, one cannot immediately become free of attachment and clinging, but one can gradually and progressively achieve freedom. If one trusts that it's possible to become cleansed of one's subtle defilements, one will strive and practice diligently. The first step is recognizing samsara's worthlessness. Having realized how futile samsara is, one automatically renounces it and becomes free of attachment.

The Special Preliminaries

1) Instructions on Taking Refuge & Arousing Bodhichitta

Having realized that samsara only entails suffering and is meaningless, one needs protection while on the path to liberation. Without a refuge and without protection, one can easily succumb to samsara's seductions and will again be at a loss. There are many types of refuge. The only true and genuine refuge is the Buddha, who is the embodiment of the Buddhas of the three times and of the ten directions. He is the only ultimate refuge. If one seeks refuge in inferior and unreliable objects, one won't be protected and won't achieve liberation.

Why is the Buddha the only reliable and lasting refuge? He has transcended all suffering and is therefore exemplary, the reason one seeks refuge in him. But, one also needs to achieve Buddhahood, the reason one needs to travel a path, which is represented by the Dharma teachings. In order to traverse the only path to lasting freedom from suffering, one needs helpers and guides on the way, which is the noble Sangha. The Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha comprise the Three Jewels of refuge. The "Anutarayogatantra Shastra" states that Buddha is the ultimate refuge and that the Dharma and Sangha are temporary. It tells us that one needs the Dharma and Sangha as long as one is on the path and that one doesn't need to take refuge in them anymore after one has attained enlightenment, while the Buddha remains the lasting refuge. Our Lama is the embodiment of the Three Jewels; in Vajrayana our Lama is the embodiment of the Three Roots, which are the Lama, Yidams, and Protectors.

When taking refuge, one visualizes a tree standing in the middle of a lake above oneself. It has one trunk pointing to a zenith and four branches pointing in the four directions from the zenith. One's Guru in the form of Vajradhara is at the top of the central trunk. On the front branch are all the meditation deities. On the branch to his right are all the Buddhas of the three times and ten directions. On the back branch are stacked the sacred scriptures. On the branch left of Vajradhara are the assembly of the Sangha; in Vajrayana, all who have reached the tenth level of realization; in Hinayana, all who have attained the levels of a Shravaka. Around the lower portion of the tree are all Dharma Protectors. All objects of refuge are before us in space. We are surrounded by all living beings and take refuge together with them in the Buddha, the sacred Dharma, and the noble Sangha.

One then recites the Bodhichitta prayers of aspiration and application. At first, one generates the wish and intention to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all living beings and promises to attain the goal, which is to attain Buddhahood and to establish all living beings in that state too. Then one generates determination to put one's wish into practice by reciting the Bodhisattva prayer of application.

One recites the refuge prayer while doing prostrations. Why are prostrations carried out? Followers need an effective practice to truly renounce samsara. In "The Four Dharmas of Lhaje Gampopa," one prays: "Grant your blessings so that my mind may become one with the Dharma." Of course, one can turn one's mind towards the Buddhadharma, but one needs to engage in a physical practice, the reason one does the prostrations - it is a practice that will help one overcome pride and achieve the aim.

Some people think that they will become famous and powerful or that they will have many disciples if they practice the Dharma, and they practice with such aims in mind. This is not correct. One prays the refuge and Bodhichitta prayers as a means to generate and uphold a pure attitude so that one's practice is not polluted by selfishness. By taking refuge while doing prostrations, one's practice is blessed by all Lamas of the Transmission Lineage. One sincerely asks them to grant their blessings and to offer their protection from the suffering that samsara entails by reciting the Bodhichitta prayer, which is: "Just as all previous Buddhas and Bodhisattva developed Bodhichitta and attained enlightenment, we too promise to generate and practice Bodhichitta."

2) Meditating Vajrasatta

Meditating Vajrasattva, Dorje Sempa in Tibetan, is practiced in order to purify all negative karma one has amassed since beginningless time. This practice is essential to cleanse and eliminate all negativities in one's mind. It wouldn't be enough just to stop engaging in negative actions while striving to reach enlightenment, because many strong habitual tendencies would still be stored in one's mind and would give rise to further disturbing emotions that repeatedly cause one to behave badly. Therefore, merely thinking one is free will not do. One needs to engage in a purification practice.

The special purification practice taught in Vajrayana is that of Dorje Sempa. He embodies the power of all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to purify one of negative karma. It is due to the kindness of our Lama, of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that we can purify all our past negativities through the meditation practice of Dorje Sempa. However, purification alone is not enough to attain enlightenment, since one also needs to accumulate merit

3) Making Mandala Offerings

The third preliminary practice is offering a Mandala, which is performed in order to accumulate merit. There are two kinds of meritorious accumulations: the accumulation of merit with concepts and the accumulation of merit with wisdom, i.e., without concepts. Offering a Mandala is accumulating both kinds of merit.

The rice used in making a Mandala and the visualizations one does are the accumulation of merit with concepts. Imagining the continents, the precious offerings, and so forth is still associated with the three references that are subject, object, and action, called the three spheres. While performing the Mandala offering, one imagines offering to all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. But one needs to transcend ordinary concepts and realize non-duality, i.e., the unfabricated state, which is realization that there is no subject, object, and action and is the accumulation of wisdom. In the practice, one places rice on the offering plate and imagines making a vast variety of wonderful offerings to all Lamas, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas. Making offerings is an act of accumulating merit.

The completion phase of practice is imagining that the field of merit, i.e., the objects of veneration before us, melts into us. This stage of practice is the accumulation of wisdom, since one doesn't cling to a subject, to an object, and to actions anymore, and therefore it is perfect purification. Usually one makes outer offerings consisting of candles, incense, water, and so forth, inner offerings consisting of the five meats and the five nectars, and secret offerings. The ultimate offering is Mahamudra.

The visualization is the same as that carried out while taking refuge and arousing Bodhichitta, except in this practice one doesn't imagine the Refuge Tree. One can place the Mandala with five heaps of rice on the shrine, which is called the Shrine Mandala, or one can imagine that the Mandala is present, which is called the Offering Mandala. Having performed the entire ceremony as often as possible while reciting the liturgy, the visualized field of merit dissolves and melts into oneself and then one rests in non-referential evenness, free of the concepts of a subject, objects, and an action.

The path of Dharma consists of purification and accumulation practices. Dorje Sempa meditation is the purification practice and the Mandala offering is the accumulation practice.

4) Practicing Guru-Yoga

The practice of Guru-yoga is the last of the four special preliminaries by which one develops untainted, heart-felt devotion and faith in one's Lama. Purification of one's obscurations and accumulation of merit alone do not engender Buddhahood. One needs the inspiration and blessings of one's Lama and all Lamas of the Oral Transmission Lineage, the reason one practices Guru-yoga. It's one of the most important practices. In the beginning, one's devotion and trust are artificial since one applies effort. An advanced practitioner cultivates pure faith and devotion through the practice of Guru-yoga.

Having visualized according to the instructions, one recites "The Seven-branched Prayer." One (1) pays homage and prostrates to all Lamas of the Lineage, which counteracts pride; (2) makes offerings, which counteracts miserliness and greed; (3) confesses negative actions, which counteracts aggression; (4) rejoices in the good of others, which helps one overcome jealousy; (5) requests the Lamas, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas to remain in cyclic existence and to teach the Dharma in the world, which counteracts ignorance; (6) beseeches them not to pass into Parinirvana, which counteracts having wrong views; and (7) dedicates the merit that has arisen through one's practice for the welfare of all sentient beings, which leads to Buddhahood. Having recited the prayer and meditated according to the instructions one received from one's Lama, one rests united with one's Lama.

Guru-yoga is practiced in order to stabilize and increase one's confidence and devotion. One recites the prayer to one's Lama as often as possible and before uniting with him during each session. While practicing, one requests one's Lama's blessings so that one becomes free of attachment to samsara, realizes renunciation fully, and achieves the ultimate state of Mahamudra.

Summary

The four special preliminary practices make one a fit vessel for the Dharma. It's only possible to attain enlightenment if one has the qualifications, which one gains by practicing the preliminaries correctly. If one has completed the preliminaries in reliance on one's Lama's instructions, one advances to further practices. If one hasn't completed the general and special preliminaries, one isn't ready for the advanced practices of calm abiding and special insight meditation. Mahamudra practice begins with the preliminaries, the reason they are called Ngöndro, which means "(that which) goes before."

II. THE MAIN MEDITATION PRATICES

Before continuing with the teachings, I want to ask you to give rise to ultimate Bodhichitta, which is the wish to benefit others, and to keep this wish in mind while engaging in Dharma activities and at all times.

The practice of Mahamudra is divided into three sections: the four general contemplations that move one to renounce samsara and the four special practices that are taking refuge and arousing Bodhichitta, meditating Dorje Sempa, making Mandala offerings, and meditating Guru-yoga. The central part of the text "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya" deals with calm abiding and insight meditation and both lead to profound meditative concentration, called samadhi in Sanskrit. The last part deals with enhancing one's practice and dispelling hindrances.

When Lord Buddha turned the Wheel of Dharma, he taught that there are three phases: (1) One first needs to hear the teachings; (2) then one needs to contemplate the meaning until one understands the teachings well; (3) finally, one needs to meditate the meaning of the teachings. One must put all teachings into practice in order to fully integrate the Dharma in one's life. Whatever practice one does, it must be carried out according to the three stages of hearing, contemplating, and meditating the instructions.

There are two ways to unite the view won by hearing and contemplating the teachings with meditation. The first is learning about the truth of phenomena and about the nature of the mind and then meditating so that one experiences the teachings one has intellectually understood. The second approach is meditating so that one realizes the truth of phenomena and the nature of the mind and thus attains the perfect view of the teachings.

If one chooses to first study the Dharma before meditating, one listens to the instructions and reflects them for a long time. Having acquired a keen mind, when such a practitioner later meditates, he or she will have direct realization of the nature of reality. This approach isn't fitting for everyone, though, since an intellectual understanding brings with it the danger of clinging to concepts and would then stand in contradiction to the meditation instructions. The second approach is recommended in the Karma Kagyü Tradition in that one meditates and in the process gradually attains the correct view.

Actually, the first as well as the second approach lead to the same result, which is realization of one's mind's true nature, but it's a practical matter. One can become very confused by only winning an intellectual understanding. Certainly, one can understand the words without understanding the meaning. By practicing the second approach, one experiences the meaning while meditating. Mind's nature is ineffable and can only be realized experientially. Therefore, meditation practice is central in the Karma Kagyü Tradition. A theoretical understanding of enlightenment does not bring enlightenment. One needs to meditate. Why?

Samsara is caused by confusion. Sentient beings steeped in samsara experience a conflict between an apprehending subject and apprehended objects, are therefore confused and suffer. One's mind creates samsara, and it cannot be overcome by the use of words. One needs to meditate in order to uproot one's obscuring mental and emotional tendencies and habits that bring on suffering. Buddha Shakyamuni taught that one should not believe the words he spoke, but one needs to understand the meaning if one wants to become free of one's deceptive way of apprehending. If one merely focuses one's attention on the words that are spoken during teachings, one will never become free. Words do not have the power to liberate anyone from suffering that one creates due to one's confusion, rather one must realize the meaning of the teachings by meditating them correctly. This leads us to the next chapter of the text, in which the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa explained calm abiding and special insight meditation. Numerous kinds of meditative concentration are experienced through the practice of calm abiding and special insight meditation. If one studies and meditates, one will be able to attain reflexive pure awareness.

Calm Abiding Meditation

Calm abiding meditation, shi-gnä in Tibetan (shi meaning "calm, peaceful, tranquil") refers to mind's state during meditative concentration. Usually, one is very distracted and agitated by many experiences and impressions one encounters in daily life, and so one's mind is continuously moving and jumping about. One's mind can become peaceful through meditation, which is the meaning of the second syllable, gnä, "to abide." When one's mind abides in calm, one experiences shi-gnä, which is the first stage of the main body of meditation. One may have learned a lot about selflessness and so on, but one will never be able to realize the true nature of one's mind as long as one isn't calm. However, one will be able to see one's true nature when one's mind is calm and at ease.

All living beings have Buddha nature, but they do not realize it due to the many impeding distractions they chase after, and this is the reason one needs to meditate. One can learn not to give in to distractions and instead to rest in a state of peace and ease through calm abiding meditation. As a result, one can realize the selfless nature of all things. For example, if wind blows across the surface of a lake on a clear night, the moon will not reflect on the water. The moon reflects clearly and brightly on the surface of still water, though. Likewise, if one wants to see mind's true nature, one's mind must be calm and still. Having a calm mind is a prerequisite for Yidam and Mahamudra practices. If one's mind is churned in upheaval, one cannot see things clearly - a calm mind can. This is why one practices shi-gnä before engaging in special insight meditation. If one hasn't calmed one's mind and tries to practice special insight meditation, one will run into great difficulties. It's impossible to see one's true nature as long as one's mind is not stable and calm.

The traditional texts describe the points of the body and the points of the mind that one needs to have in order to practice correctly. They are said to be keys one holds in one's hand when aspiring to attain calm and ease.

1) Points of Body

The physical posture is most important for one's mediation to go well. There are seven points to take into consideration, called the sevenfold posture of Vairocana. He is the central Buddha in the Mandala of all Buddhas. The seven points of Vairocana are: (1) The legs rest in the full lotus posture; (2) the hands rest in equipoise below the navel or on the lap; (3) the back needs to be held as straight as the shaft of an arrow; (4) the shoulders are raised and held back and are even like the wings of a vulture; (5) the neck is slightly bent like a hook; (6) the lips are relaxed and slightly opened to the size of a rice corn; the tongue is relaxed and touches the upper palate; and (7) the eyes gaze at a point beyond the tip of the nose without moving. Some texts say that the eyes should gaze at a point four finger-lengths beyond the tip of one's nose, others recommend eight finger-lengths, others speak of sixteen. In general, a meditator looks downwards and keeps his eyes slightly opened. Beginners may meditate with closed yes, yet it is necessary to keep them open when one proceeds to more advanced practices.

Many subtle energies (rlung in Tibetan) flow within the body. Now, the subtle energies in the body are formed at birth in dependence upon one's karma. The perfect meditation posture brings the karmic energies within the channels (nadis in Sanskrit), that are arranged throughout the body, to flow into the central or main channel, which is located in front of the spine. If the energy-winds are brought to properly flow into the central nadi, the mind becomes focused, even, and calm. Furthermore, the karmic energies then transform into wisdom energy.

2) Points of Mind

Seated in the sevenfold posture of Vairocana, a practitioner needs to check his mind in order to be able to practice meditation correctly. There are many levels of shi-gnä - holding the mind without a support and holding the mind with a support. The superior practice is resting in mind itself and meditating its essence. Beginners need referential objects in order to not follow after distracting thoughts and to stabilize their mind. At a certain point, a practitioner doesn't need a referential object and can then meditate without a support, which is practiced during the intermediate stage of shi-gnä.

- Holding the Mind without a Support

It's important not to think about past events, not to anticipate the future, and not to cling to the present when one meditates. All thoughts that arise always concern the past, present, or future, called the three times. One may recollect past experiences that made one happy or sad; in any case, they are thoughts that cause one's mind to become agitated and distracted from one's meditation practice. One may anticipate the future and make plans, which are also thoughts that cause one's mind to become agitated and distracted. Or one might cling to a thought concerning the present. Due to following after thoughts, one isn't able to abide in a state of presence but clings to a thought and then chases after it, bringing on a chain of thoughts and finding oneself agitated again. When one's mind is agitated, one cannot be mindful and aware. Therefore one learns to cultivate mindfulness and awareness through the practice of calm abiding meditation. How does one practice?

When thoughts arise, one should not suppress or succumb to them by following after them and creating a chain of thoughts, rather one lets one's mind settle and rest in its natural state, in its essence, without pushing thoughts away or struggling with them. This doesn't mean that one's mind should be locked up. Meditation means becoming accustomed to not allowing oneself to be distracted. In order to stabilize awareness, a beginner focuses his attention on an object. An advanced practitioner is able to hold his attention inwards without focusing on an object.

Meditation is practiced in order to generate and cultivate mindfulness and awareness. Ideas such as, "I'm really good at meditation" or "My meditation is bad" do not apply. One doesn't fabricate and manipulate one's practice and has no expectations. Rather, one rests in calm without clinging to any feelings or thoughts. Clinging is a sign of attachment and impedes one's meditation. One's mind needs to be free of agitation, excitement, and any interruptions.

While practicing shi-gnä, one leaves one's mind as it is and rests in its presence, i.e., in nowness. While letting thoughts come and go again, one looks at a thought and abides in its empty essence. This means to say that one doesn't manipulate a thought and doesn't fight against it, rather one simply looks at the nature of a thought when it arises and discovers that it is empty of an own essence. If one succeeds, one will experience that a thought is the coemergence of appearance and emptiness, and then a thought would be liberated into itself. Should one struggle with or against a thought when it arises, one wouldn't be able to see its true nature. Should one see the true nature of a thought when it arises and rest in its empty essence, deliberateness wouldn't impede one's practice. Then one would naturally experience happiness when thoughts arise and cease again.

Just like the play of waves are a display of the ocean's nature, one lets one's thoughts arise and freely cease again. One doesn't try to manipulate them during meditation, which would disrupt one's practice. Not becoming involved with thoughts by being attached to them and giving in to hopes and fears, one experiences the unimpeded manifestation of pristine wisdom. As long as one chases after thoughts that one has, one will remain caught in the endless net that has kept one fettered in samsara up and until now. When one abides in peace and calm, one doesn't divide and thus isn't prejudiced, rather one has attained freedom from dividing between what seems to be good and what seems to be bad.

Three points need to be practiced in order to accomplish calm abiding: (1) non-wandering, which means that a practitioner is aware of arising thoughts and lets his mind rest in the awareness of the essence of each thought without discriminating or judging; (2) non-meditation, which is the superior practice at which stage a practitioner meditates, without using a referential object, but looks at the essence of his or her mind without giving in to distractions. Of course, beginners need to practice with a support. (3) The third essential point to heed while practicing calm abiding meditation is non-fabrication, i.e., nothing is manipulated or tried out in order to fulfill expectations; one lets anything that happens during meditation just happen. All meditation practices are based upon these three essential points: non-wandering, non-meditation, and non-fabrication. Mahamudra meditation can be carried out when one is able to hold one's mind on the essence of one's mind.

I will now speak about the various supports recommended for calm abiding practice.

The best kind of shi-gnä practice is just letting one's mind rest in its natural and pure state, which is the purpose of this practice. Although it might sound easy, it isn't possible for beginners. Why? Many thoughts arise and there is a constant mental activity taking place in one's mind, which a beginner can't really cope with. I explained how to deal with thoughts by just letting them arise and subside, like the waves on the surface of an ocean. I mentioned that waves aren't separate or different than the ocean; likewise, mind's thoughts aren't different than the mind. When one realizes the indivisibility of an ocean and its waves - the inseparability of active thoughts and one's mind - one needn't worry about thoughts anymore but simply looks at the mind when thoughts occur. Aware that a thought has arisen, one abides relaxed and at ease. Whether one has a thought or doesn't have a thought, one simply continues meditating.

Beginners don't realize this and think thoughts are a problem and are hindrances. They think they cannot meditate correctly because they notice their many thoughts and start worrying. This is why this text as well as all other practice instructions recommend methods that facilitate the practice of stabilizing one's mind. I have described the practice without a support, yet beginners need to practice calm abiding meditation by using a support.

- Holding the Mind with a Support

The many texts in the tradition recommend various supports. In this text, Wangchug Dorje offers a list of six objects that can be used for meditation practice.

The first object a beginner might want to focus his or her attention on is (1) an ordinary object placed in front during practice. Ordinary objects are things the mind is familiar with, small things from everyday life, like a small pebble or a piece of wood. The mind feels no excitement or agitation when focused upon such a simple and familiar object, the reason a pebble or piece of wood is suggested.

The second type of object is (2) a special object and refers to the body of the Buddha. One focuses one's attention on a representation of Buddha Shakyamuni, in the form of a statue or a painting, and lets one's mind rest on it. One will have different experiences, like mental dullness. If one thinks one is about to fall asleep, one looks at the upper portion of the statue, at the point between the eyebrows or at the crown of the Buddha's head. This helps uplift and waken one's mind from sleepiness.

Concentrating on a special object has many advantages in contrast to an ordinary object. A Buddha's body is perfect and possesses thirty-two major marks of enlightenment. One might just know two of them, which is fine for the start. A Buddha has a crown-protrusion and a circle of hair between his eyebrows. He also has the symbol of wheels on the soles of his feet, as depicted on statues. Again, it isn't necessary to know all the marks. If one is aware of a few, one can look at the statue that one has placed before one and feel happy about the image. And so, using a statue or painting of the Buddha to practice calm abiding is very good.

I mentioned mental dullness that can arise and the antidote during practice. Wangchug Dorje wrote about another error that can occur during practice, namely agitation and excitement. In that case, many thoughts arise and one's mind wanders and is instable. When such a fault occurs, one focuses one's attention on the lower half of the statue or painting, on the navel, legs, or on the lotus that the Buddha sits on. This frees the mind from excitement. Should one feel no dullness or agitation, one focuses one's attention on the entire image, rests one's mind on it, and abides in meditative equipoise.

The third kind of object one can use for shi-gnä meditation is (3) a butter lamp, about the breadth of four fingers. One leaves one's mind focused on this small butter lamp. The fourth object recommended is (4) an empty hole in the wall of a room, referring to holes that served as windows in Tibet. In this case, one concentrates on a smaller or larger window, which represents transparency and brings clarity. This object accustoms one to later be able to meditate on emptiness or space.

It is also taught that one can use (5) a drawing of the three precious and rare syllables, which are OM, AH, and HUNG. The syllable OM is white and represents the pure body of the Buddha. The syllable AH is red and is below the white OM; it represents the Buddha's pure speech. Situated under the red AH, the blue syllable HUNG represents the Buddha's immaculate mind. One simply lets one's mind rest on each of the three syllables successively, using them as a mental support to achieve calm and ease. One can also focus one's attention on white, red, and blue spheres drawn on a piece of paper, which is easier than using the syllables. The sixth object Wangchuk Dorje suggested is (6) one's breath. One just lets one's mind rest on one's inhalation and exhalation.

Except for the sixth, all recommended objects are external and can be placed before one, the reason they are called external. One uses external objects to focus one's attention on during shi-gnä practice in order to stabilize one's mind. One is free to decide which object one wants to use so that one feels comfortable.

During practice, how does one relate with the object one chose? The main point is just letting the mind rest on the specific object without wandering from it. Distracting thoughts that arise are such thoughts, like, "My mind feels stable," "My meditation is very good," "Now I'm having difficulties," "I do hope all goes well," or "I do fear experiencing the same as I did yesterday," and the like. While meditating, it's necessary to just let thoughts be. They aren't important, so one returns to the referential object.

Special Insight Meditation

When one sits in the sevenfold posture of Vairocana, one's body is relaxed because all tension that arises on account of having hopes and fears has been pacified. If the body is relaxed, the mind is also naturally calm and clear. If one's body is relaxed, meditation comes easily and one experiences less agitation that anxiety brings on.

Having trained to abide in non-distraction for a while, one progresses to more subtle objects of attention, such as objects of the five sensory faculties. One first rests one's mind on a visual object and remains aware of it without being distracted. Then one rests one's mind on a sound in the same manner, on a smell, on a taste, and finally on a tactile sensation one feels with one's skin, such as heat, cold, smoothness, or roughness. During this practice, three thoughts occur in reliance on (1) the mental consciousness, (2) the referential object of practice, and (3) the respective sensory perception that arises due to a sensory faculty. All apprehensions involve these three aspects: a sensory organ, a perceived object, and the respective consciousness. One uses them in practice.

At this point we might ask: Why do we have an animate mind and an inanimate body? In which way are they related? How do they support each other? What happens at death? As Buddhists, we know mind takes on a new body after death. We know death is very frightening and know that our body disintegrates when we die. How is the mind without a body? Can a mind exist without a body? These questions concern the fourth aspect of practice, which is (4) meditating the relationship between body and mind.

The fifth aspect of practice is (5) watching the wandering and stable mind. One watches one's mind while practicing calm abiding meditation. One watches one's mind when it is agitated and asks, "Is it the same mind when it is active and when it is at peace? Are both aspects two different minds?" One investigates carefully and discovers that one's moving thoughts are like the waves on the ocean's surface. Aware that the fluctuating waves do not change or impede the ocean, one knows that an ocean is always an ocean, whether there are waves or not. Likewise, one's mind is always one's mind, whether one is in a state of agitation or at ease. And so, one realizes that the perturbed mind and the stable mind are one and the same.

III. REALIZING FRUITION

I don't want you to only win an intellectual understanding of the Dharma. Of course, one needs to learn the practices, but it's more important to look at the mind, integrate the practice in one's life, and discover what the mind really.

Mind's essence is emptiness possessing self-awareness of manifestations, referred to as all-pervading and unobstructed, i.e., emptiness and lucidity. Mind's nature is the inseparability of emptiness and clarity. Through meditation practice, one comes to realize that there is no mind different than thoughts and that there are no thoughts different than the mind. One realizes that one either recognizes the mind or doesn't, whereby both are the same mind. Differences pertain to realization. One needs to look at one's mind in order to realize that it is in truth free of an apprehending subject and apprehended objects. Realization of the union of emptiness and clarity - which is freedom from subject and objects - is Mahamudra, the goal of all meditation practices. Words will not disclose Mahamudra. One needs to purify one's negativities and obscurations that conceal one's mind's true nature and accumulate merit in order to realize Mahamudra. How does one do this? By perfecting the preliminaries and by practicing the main body of instructions that are taught in "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya."

Many unskilled practitioners think they can jump into higher practices and engage in Yidam and Mahamudra practices without having perfected the preliminaries, but this will be very detrimental to achieving fruition. Should one meditate on the nature of one's mind without having perfected the preliminaries, all efforts are in vain. One needs sincere faith, confidence, and certainty of karma, and one needs perfect renunciation in order to meditate Mahamudra correctly. Of course, one can receive many teachings on Mahamudra, but it would only be like changing old clothes as long as one has failed to prepare the ground properly. It's necessary to actually integrate all teachings in one's life and to know that they are only presented in order to help one transform one's delusive apprehensions into peace and supreme insight. This can only happen if one relies on and is dedicated to one's Root Lama, if one has unwavering love and compassion, if one has ethics and engages in virtuous activities, and if one practices the methods correctly. Methods are only effective if long-standing habitual patterns have been overcome and if merit has been accumulated. And so, the preliminaries are indispensable for advanced practices.

Conclusion

I did not teach all the details of the text "Pointing Out the Dharmakaya" due to the limited time at our disposal and due to the various inclinations that the participants of this seminar have. Therefore, I presented the essential themes as a key, which everyone is free to use and put into practice.

I want to stress the importance of cultivating faith and renunciation instead of merely reiterating, "Everything is only mind." All practices are in vain as long as one doesn't have sincere faith, renunciation, and Bodhichitta. One can hear many teachings, but one needs to cultivate the ground on which one aspires to integrate the Dharma in one's life, by purifying one's obscurations, by accumulating merit, and by completing the preliminary practices. Otherwise one will not be able to understand the teachings and will remain a victim of one's emotional instability, thus prolonging one's attainment of liberation from suffering.

We can say that supreme renunciation is the essence of a Buddha. It is stated in the "Uttaratantra Shastra": "In Buddhahood there is no differentiation. It is brought about by true elements of reality. Luminous and clear like the sun and sky, it is marked by renunciation and pristine awareness." Thank you very much.

Dedication

Through this goodness may omniscience be attained

And thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome.

May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara

That is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

By this virtue may I quickly attain the state of Guru Buddha and then

Lead every being without exception to that very state!

May precious and supreme Bodhicitta that has not been generated now be so,

And may precious Bodhicitta that has already been never decline, but continuously increase!

Long-life Prayer for Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche the Fourth

May the life of the Glorious Lama remain steadfast and firm.

May peace and happiness fully arise for beings as limitless in number as space is vast in its extent.

Having accumulated merit and purified negativities,

May I and all living beings without exception swiftly establish the levels and grounds of Buddhahood.

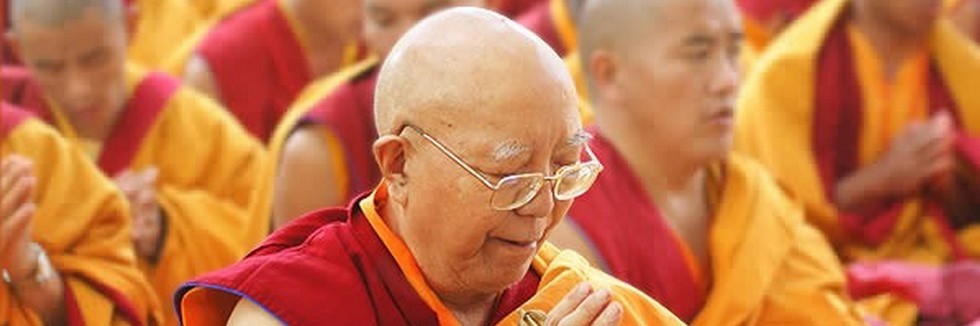

Presented in France in 1990; translated from Tibetan by Ani Lama Rinchen, transcribed in 1990 & edited again on New Year's Eve 2008 by Gaby Hollmann, responsible for any mistakes. Photo of Rinpoche courtesy of Lee. Copyright Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang at the Great Monastery of Pullahari in Nepal, 2008. All rights reserved.