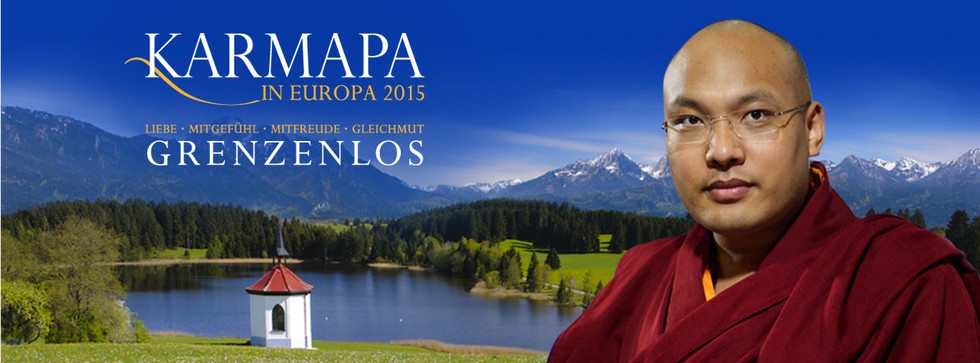

Instructions on the Vajra Doha

His Eminence the Third Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche,

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge

"The Conversion of the Scholar Lodün"

by Jetsün Milarepa

Introduction

It is a pleasure for me to return to the Kamalashila Institute. This is my second visit and I would like to greet everyone who has been able to come kindly. I wish to speak about the doha, the "song of realization," that was composed by Jetsün Milarepa and has been translated into English as "The Conversion of the Scholar, Lodün." Before I begin, though, I wish to remind you to give rise to the pure motivation while receiving these instructions. We do not only wish to receive the teachings in order to understand Buddhism and for our own well-being, but in order to be able to help a limitless number of sentient beings. The altruistic motivation is the wish to receive the teachings so that we can truly help others.

In order to practice the Buddhadharma correctly, though, one first needs to understand the view. Without understanding the view, a devotee will not know if they are correctly practicing the path that Lord Buddha showed. Integrating the view in one's life flawlessly and practicing the path of meditation correctly lead to fruition, which is Buddhahood. In this doha, which we will simply refer to as "The Conversion," Jetsün Milarepa described the view and practices that lead to fruition to the monk Lodün. I think an understanding of this profound song of realization will deepen your knowledge of the Mahamudra view, path of practice, and fruition.

Root Text: "The Conversion of the Scholar, Lodün"

Translated by C.C. Chang, in: The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa, 2 volumes, Shambhala Publications, Boston & London, 1977, vol. 2, pages 498-506.

Obeisance to all Gurus!

Listen to me, Lodun and you others, know you what mind-projection is?

It creates and manifests all things.

Those who do not understand ever wander in Samsara.

To those who realize all appears as the Dharmakaya.

They need search no more for another View.

Know you, Venerable Monk, how to set your mind at rest?

The secret lies in letting go –

Making no effort and doing nothing,

Letting the mind rest in comfort,

Like a child asleep at ease, or like the calm ocean without waves …..

Rest, then, in Illumination, like a bright and brilliant lamp.

You should rest your mind in peace, corpse-like without pride.

Rest your mind in steadfastness; like a mountain, do not waver.

For the Mind-Essence is free from all false assertions.

Know you, Venerable Monk, how all thoughts arise?

Like dreams without substance, like the vast rimless firmament, the moon reflected in water, the rainbow of illusion – like all these they arise.

Never consciously deny them, for when the light of Wisdom shines they disappear without a trace, like darkness in the sun.

Know you, Venerable Monk, how to cope with wavering thoughts?

Versatile are flying clouds, yet from the sky they're not apart.

Mighty are the ocean's waves, yet they are not separate from the sea.

Heavy and thick are banks of fog, yet from the air they're not apart.

Frantic runs the mind in voidness, yet from the Void it never separates.

He who can ‘weigh' Awareness will understand the teaching of Mind-Riding-on-the-Breath.

He who sees wandering thoughts sneaking in like thieves will understand the instruction of watching these intruding thoughts.

He who experiences his mind wandering outside will realize the allegory of the Pigeon and the Boat at Sea.

Know you, Venerable Monk, how to act?

Like a daring lion, a drunken elephant, a clear mirror, and an immaculate Lotus springing from the mind, thus should you act.

Know you, Venerable Monk, how to achieve the Accomplishments?

The Dharmakaya is achieved through Non-discrimination;

the Sambhogakaya through Blissfulness,

the Nirmanakaya through Illumination,

the Svabhavikakaya through Innateness.

I am he who has attained all these four Kayas, yet there is no flux or change in the Dharmadhatu.

Explanation of the Root Text

The scholar Gendün Lodün had received meditation instructions from Jetsün Milarepa and returned to him for further advice after having practiced a while. He first paid homage and then told his teacher that he had great difficulties practicing calm abiding meditation, because so many thoughts arose in his mind. Milarepa responded with the song of realization that I wish to speak about and said

"Obeisance to all Gurus!

Listen to me, Lodun and you others, know you what mind-projection is?"

In this song of realization, Jetsün Milarepa first offered homage to all Gurus and then addressed the scholar Lodün and his assembled pupils by asking them whether they knew what phenomena really are. He then proceeded and taught them that all apparent phenomena and experiences are not different than one's own mind, that nothing is false in itself, and that one needs to realize mind's true nature in order to become free from all inadequacies of conditionality, samsara. He defined the mind and its manifestations in the brief line:

"It creates and manifests all things."

As long as one does not know that all experiences and apprehensions are by nature an expression of one's own mind, one falsely sees phenomena as though they exist of their own accord. As a result, one clings to what is apprehended and the one who apprehends, divides every experience and appearance into subject and object, and thus sets up a barrier between what one defines as "self" and "other." This active process is the source of samsara, which is marked by pain and delusion. Therefore Milarepa told the assembly of students:

"Those who do not understand ever wander in Samsara."

The essence of all things that arise and appear is emptiness, i.e., due to emptiness (that is a lack of impediment) all relative realities clearly arise and appear when causes and conditions prevail. While one perceives objects as though they exist of their own accord and not dependent upon other things, one clings to them as though they are independent and permanent. Delusion means dividing inner and outer apperceptions, which is the source of suffering and pain, samsara.

Delusiveness causes one to believe and ideate permanent existence to experiences and appearances, which means having an eternalistic view – one extreme supposition. Or delusiveness causes one to negate the reality of conditioned existence, which means having a nihilistic view – another extreme supposition. Based upon hopes and fears, attachment and aversion evolve and give rise to further afflicting emotions that govern one's everyday life in the realm of pain, anguish, and woe.

The Third Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, perfectly described in which way beings remain entangled in samsara by clinging to erroneous views about truly existing objects in opposition to a truly existing self. He wrote: "The own appearances that never existed are eluded as objects. Through the power of ignorance, the sense of self is eluded as the subject. Driven by the force of clinging to duality, we wander in the vast realm of cyclic existence." This short verse clearly explains how samsara churns and burns by believing and insisting that apparent realities are separate from one's own mind, in other words, by believing and insisting that one's own mind stands apart from and in opposition to the world. Therefore Milarepa taught his disciples that when a practitioner of Lord Buddha's instructions realizes the true nature of everything and has nondual awareness, then

" all appears as the Dharmakaya.

They need search no more for another View."

Abstract and concrete phenomena only appear because they lack inherent, independent existence. The absence of inherent existence is called "emptiness," which means to say that every perceivable and conceivable phenomenon is empty of independent existence and therefore can arise and appear. Everything that appears has characteristics. Acknowledging and becoming aware of the nature of appearances enables one to appreciate the relative truth of reality. By unmistakably becoming aware of the fact that the essence of all appearances and experiences is emptiness and that the nature of emptiness is the manifestation of things that arise when causes and conditions are present, a student realizes the ultimate truth of reality - the unimpeded expression of the nondual Dharmakaya.

The Sanskrit term Dharmakaya consists of two words. Dharma is chös in Tibetan and means "any phenomena that can be experienced, thought of, or known." Kaya is sku in Tibetan and means "body, form, dimension of existence, enlightened form, embodiment of numerous qualities."

Reality is free of the four extreme views that things are inherently existent, non-existent, both, or neither. Reality is not touched by the eight erroneous mental formulations of mind or phenomena having such intrinsic attributes as arising and ceasing, being singular or multiple, coming and going, being the same or being different.

There is no contradiction to the fact that all appearances are empty while they clearly appear - the most important theme a student of Buddhism needs to understand and appreciate. In the absence of superior knowledge (prajna in Sanskrit) emptiness might be interpreted as being a nothingness, a blank. Emptiness, in truth, is the fact that all things are beyond the four extreme views and eight erroneous mental formulations. When a practitioner realizes reality, "… all appears as the Dharmakaya." Then a disciple "need search no more for another View."

While dividing apprehensions into "self" and "other," living beings separate relative and ultimate reality and lead their lives with the intention to change things instead of learning to find a purpose in their life. If a practitioner investigates thoroughly, he and she eventually realize that relative appearances and ultimate reality are not opposites but coexist. Again, since appearances lack independent, inherent existence, they appear clearly, i.e., dharmas only appear because they are empty of inherent, self-existence.

Having the pure view means seeing the indivisibility of emptiness and manifestations. The ultimate view that Lord Buddha invited us to investigate and freely integrate in our lives is not an intellectual fabrication. The purpose of practice is to learn not to cling to either emptiness or clear manifestations. Disciples can win certainty of the ultimate view so that they are able to easily engage in reliable methods while traversing the path to freedom from conditionality, samsara. It is quite difficult to practice the path of liberation without having the pure view. The pure view means having nondual awareness that nothing whatsoever is separate from one's own mind and that relative and ultimate reality indivisibly coexist.

"Know you, Venerable Monk, how to set your mind at rest?

The secret lies in letting go –"

Jetsün Milarepa then asked his disciples if they knew how to place their mind in tranquillity. Not knowing how to settle the mind in calm-abiding (shamata in Sanskrit) one follows after thoughts that incessantly arise in one's mind. A practitioner needs to leave the own mind in its natural state and not follow after fabricated distractions by chasing after thoughts that do occur and as a result fracturing his or her self-sense into a subject versus objects.

"Making no effort and doing nothing,

Letting the mind rest in comfort,"

In this short verse, Milarepa taught his disciples that fabricating a meditation practice by forcing oneself not to think leads to mental dullness and thinking that thoughts can be transformed brings on agitation. It is very hard for beginning practitioners of meditation to rest their mind in evenness, therefore they are instructed to focus their attention on a specific object during formal meditation practice.

In "The Aspiration Prayer of Mahamudra," the Third Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, also tells us that the mind needs to be free of contrivances. Mahamudra actually means settling one's mind in non-discursive and non-fractured evenness. The Third Karmapa explained the purpose of Mahamudra practice in "The Aspiration Prayer" and wrote: "The waves of coarse and subtle thoughts are pacified in themselves: Mind's steadfast continuum abides in itself. Free from the mud of drowsiness and agitation, may the unperturbed sea of evenness become firm and stable." By becoming accustomed to resting in evenness and ease, a practitioner's mind becomes used to abiding in its natural nature. When an advanced practitioner achieves this result, there is no longer a difference – for him and for her - between meditating and meditator.

Jetsün Milarepa offered metaphors to show his disciples how resting the mind in its true nature actually is and sang:

"like a child asleep at ease, or like the calm ocean without waves."

A little child is not concerned about thoughts such as, "This is a good thought and that is a bad one" - an infant does not nourish similar hopes and fears. Likewise, a mind abiding in comfort and ease resembles a still ocean that is not perturbed by waves that arise on its surface. This means to say that one's mind should not be moved by arising and subsiding waves of thoughts.

Milarepa offered further examples on how mind really is and needs to be so that a practitioner experiences his or her own mind's true nature and sang:

"Rest, then, in Illumination, like a bright and brilliant lamp.

You should rest your mind in peace, corpse-like without pride.

Rest your mind in steadfastness; like a mountain, do not waver.

For the Mind-Essence is free from all false assertions."

The metaphor in the first line illustrates that a mind resting at ease is like the light of a candle that illuminates everything around - all the more clearly if it is not disturbed by wind. In the second line Milarepa taught his students to rest their mind in the peace that resembles a corpse so that they become free of pride. He also taught that the true nature of the mind is like a steadfast mountain; should thoughts arise, a practitioner needs to remain just as unshakeable as a mountain and not be swayed by thoughts. He described the mind's essence in the same verse and said that if a disciple is able to abide in unwavering naturalness, then the mind's true nature manifests clearly.

The essence of samsara and nirvana is non-differentiate - relative and ultimate reality coexist. Therefore Milarepa taught his disciples how to practice and explained that a disciple who is able to train his or her mind will achieve nondual awareness and experience the indivisibility of samsara and nirvana.

"Know you, Venerable Monk, how all thoughts arise?

Like dreams without substance, like the vast rimless firmament, the moon reflected in water, the rainbow of illusion – like all these they arise.

Never consciously deny them, for when the light of Wisdom shines they disappear without a trace, like darkness in the sun."

I addressed the fact that no apparent phenomenon is separate from the mind, that all things in and around us are clear manifestations of our own mind. It is necessary to hold the mind in its natural state of ease so that one can experience the true nature of one's own mind, which is always and ever luminous light, like the sun that dispels darkness.

All thoughts that arise are by nature empty of inherent existence and without a substantial essence. We saw that emptiness isn't a mental construct that enables a practitioner to eliminate thoughts by sweeping them away. It is necessary to acknowledge and realize that thoughts simply arise and cease again due to emptiness. Then it is possible to just let them be.

"Know you, Venerable Monk, how to cope with wavering thoughts?

Versatile are flying clouds, yet from the sky they're not apart.

Mighty are the ocean's waves, yet they are not separate from the sea.

Heavy and thick are banks of fog, yet from the air they're not apart.

Frantic runs the mind in voidness, yet from the Void it never separates.

He who can ‘weigh' Awareness will understand the teaching of Mind-Riding-on-the-Breath.

He who sees wandering thoughts sneaking in like thieves will understand the instruction of watching these intruding thoughts.

He who experiences his mind wandering outside will realize the allegory of the Pigeon and the Boat at Sea"

Jetsün Milarepa's disciples practiced and continue practicing calm-abiding meditation in order to abide in mental comfort and ease that is free of abstract thoughts that have no beneficial meaning in life. They learn to pacify their own mind by engaging in tranquillity practices and always realize that thoughts certainly distract the very moment they arise. A skilled practitioner of Mahamudra is not taught to stop thoughts when they arise, since they are not different than the own mind. Momentary thoughts are not separate from the true nature of one's own mind, since their essence is empty of inherent existence, i.e., their essence is emptiness. Thoughts as such are not deluded and responsible for samsara, rather clinging and chasing after them is a barrier one sets up, which distracts and brings on delusion. As long as one reifies concepts and thoughts, one remains fettered in samsara.

By letting thoughts be, one discovers their innate qualities, which is primordial wisdom. Timeless awareness (yes-shes in Tibetan) naturally shines forth when a practitioner realizes the essence of thoughts the moment they arise. Since they are the expression of primordial wisdom, thoughts need not be eliminated or swept away when they arise so that primordial wisdom manifests in one's mind. When an advanced practitioner leaves thoughts as they are, without reifying or denying them, he and she spontaneously experience their true nature, which is the indivisibility of emptiness and primordial wisdom that is timeless awareness.

The Mahamudra instructions do not tell us to conceive realms of transcendence or to reject inadequacies of conditioned existence, rather to become aware of thoughts the moment they arise. Usually this is not the case, and, instead, human beings fail to recognize that everyday life is governed by thoughts they have become used to over a very long period of time and desperately cling to out of habit. Conceiving realms of transcendence beyond everyday life impedes realization of one's own mind's true nature. Mahamudra does not mean blindly following after thoughts that occur and thus generating even more, rather it means recognizing thoughts as they occur.

Realization of Mahamudra means abiding in the ease of wakeful awareness, free of any suppositions concerning who one thinks one is and who one wants to be, free of any beliefs concerning a subject observing an object, in this case one's own mind. Conceiving subject and object impedes realization of Mahamudra and denotes dividing one's apprehensions into "self" and "other." Mahamudra is never divided; it is realization of the indivisibility of emptiness and luminosity – the manifestation of Buddha activity. Mahamudra is very profound. It is the reality of everything that is and can be.

In The Conversion, Jetsün Milarepa taught that thoughts are like dreams. Now, dreams are an illusion, even when one clings to them as real while asleep. Likewise, thoughts are an illusion, even when one clings to them as real while not wakefully aware. Milarepa compares thoughts with the moon's reflection on a body of water; it manifests clearly, but the image reflected on the water's surface is not real. Likewise, thoughts arise from the mind but aren't real. Let me repeat that thoughts as such are not good or bad - they are empty of inherent existence.

Jetsün Milarepa offers another analogy and compares thoughts with a rainbow that consists of different colours. A rainbow cannot be grasped or held; it, too, does not truly exist. Likewise, the variety of thoughts resemble a rainbow that naturally subsides into the sky after a short while. Furthermore, waves are not separate from the ocean; they arise and subside into the ocean after a short while. Likewise, thoughts arise from the mind and naturally subside into the mind after a short while. This is the reason why thoughts do not create samsara, rather clinging to thoughts creates all experiences of frustration, suffering, and woe.

It is important to realize that thoughts are a manifestation of mind's clarity the moment they arise and not to follow after them by associating them with the past, present, and future. A Mahamudra practitioner simply watches – wakefully aware - thoughts arise, abide, and naturally subside into the mind all on their own.

"He who sees wandering thoughts sneaking in like thieves

will understand the instruction of watching these intruding thoughts".

Milarepa sincerely teaches his disciples that it is necessary to deal with thoughts in the most precious song of realization, The Conversion. It is so important to understand that thoughts are like thieves; it is also important to be aware of them when they arise and to see them as robbers who steal one of comfort and ease. A thief is only a thief, though, as long as one sees him as such and responds. If a practitioner does not respond and retaliate when a thief sneaks in, then even thoughts about him will subside and as a result there is no thief anymore.

Usually, human beings are not aware of thoughts that arise and unconsciously respond to them, intensifying mental distractions as a result. It is important to recognize thoughts when they arise and not to fall into a fractured state by becoming involved and therefore governed by them. Instead, a successful practitioner rests in comfort and ease and remains mindful and aware, no matter what thoughts arise.

"He who experiences his mind wandering outside

will realize the allegory of the Pigeon and the Boat at Sea."

Jetsün Milarepa compared thoughts with a blackbird that lands on a boat at high sea, far away from land, far away from any distractions that cause the mind to wander and sway. The mind flies away when it chases after thoughts that arise instead of watching mind itself. Just like a blackbird will always return to the ship on the great ocean, mind will always return to the mind. The Tibetan original speaks of a blackbird.

"Know you, Venerable Monk, how to act?

Like a daring lion, a drunken elephant, a clear mirror, and an immaculate Lotus springing from the mind, thus should you act."

Milarepa offers examples on how a disciple of Mahamudra acts while remaining in tranquillity in this short verse. He and she act like a lion who personifies fearlessness, and like an elephant, who personifies determination. An elephant doesn't hesitate a moment when it is mad and becomes wild. Milarepa also compares the mind with a clear mirror that reflects anything clearly and directly. So, a trained practitioner acts fearlessly, spontaneously, and clearly. A beautiful lotus flower grows in murky waters and dirty ponds. Likewise, a successful practitioner acts free of any outer influences that are impediments.

"Know you, Venerable Monk, how to achieve the Accomplishments?

The Dharmakaya is achieved through Non-discrimination;

the Sambhogakaya through Blissfulness,

the Nirmanakaya through Illumination,

the Svabhavikakaya through Innateness.

I am he who has attained all these four Kayas, yet there is no flux or change in the Dharmadhatu."

In this verse the Jestün described fruition of practice, which is realization of non-discursiveness, bliss, and clarity.

Realization of emptiness is realization of the Dharmakaya. I spoke about the fact that emptiness is not a blank, dull, non-reflective mental state, rather that emptiness is what makes it possible that everything - qualities of being, too - manifests freely when causes and conditions prevail. The unsurpassable qualities of the Sambhogakaya are bliss and joy; the limitless qualities of the Nirmanakaya are unimpeded presence that helps living beings; the indescribable qualities of the Svabavikakaya, that is the indivisibility of the other three Kayas, are manifestations of Dharmadhatu, the innate expanse of reality that is our mind's true nature.

In "The Conversion of the Scholar, Lodün," Milarepa generously described the view, meditation practice, and conduct that a practitioner of the Buddhadharma recognizes and makes real - the essence that is his and her own mind, always and already present since the very beginning of beginningless time.

Questions & Answers

Question: Is it necessary to change our attitude about phenomena, which are as reflections of the moon on water and like dreams?

Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche: Yes, it would be very good. As it is, you experience dreams as real while you sleep and recognize that a dream was merely a dream after you wake up. Likewise, while awake we think that all phenomena are real. When the true nature of reality has been realized, then everything is experienced like a dream.

Question: I am wondering how you see phenomena?

Rinpoche: All apparent phenomena and experiences clearly appear and are neither pure or impure. As long as a practitioner has not seen the truth, he or she distinguishes between pure and impure things. Seeing the essence is seeing that apparent reality is neither good nor bad. Realization isn't a conceptual understanding but an experience.

Question: What happens when a woman achieves realization?

Rinpoche: The activities of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas benefit all living beings. Does that answer your question?

Student: There are a few realized women, though.

Rinpoche: A student of the Buddhadharma generates and develops Bodhicitta, the altruistic intention to benefit others. Actions carried out with Bodhicitta aren't restricted to men and cannot be divided into male and female activities. Bodhicitta is the benevolent mind of those persons who can help others and manifests in dependence upon conditions. Both men and women can have the same intention.

Question: How does one acquire the right view to practice shamata correctly?

Rinpoche: Are you asking how to get it?

Student: Yes, through study or practice?

Rinpoche: Both. It is first necessary to learn about the correct view and to know how to distinguish it from wrong views. Once you have won certainty of the view, you need to apply it in practice. As I said, you find meditation through the right view, and you find the right view through right meditation. In order to meditate properly, though, you need an intellectual understanding of the right view, otherwise you may not have the right meditation. Once you have a good understanding, then you apply it to practice and the view becomes alive as a result.

Question: How do I know that I have the right view to practice correctly?

Rinpoche: It is important to learn the correct view from an authorized teacher who understands it well. While practicing the path of meditation, you need regular instructions from your teacher. This is why it is so important to have qualified teachers. False notions can arise while practicing the path and then a teacher needs to help you.

Student: Does the teacher one trusts have to be a fully realized individual?

Rinpoche: There are different categories of teachers: an ordinary person, a Bodhisattva, or a Tulku. The choice of a teacher depends upon a student and upon the qualities that a teacher has. If someone trusts a teacher, they have a reason to do so. Someone who isn't fully qualified but has an enlightened teacher is a valid teacher. It really isn't possible to give a general answer to your question, seeing a teacher is judged subjectively. You need to investigate for yourself.

Question: How do you know that you can rely on one Lama instead of on many?

Rinpoche: You can learn Lord Buddha's teachings from many Lamas. In Vajrayana, we have the Root Guru. He is the master who introduces disciples to the true nature of their mind, and students then truly realize their mind's true nature. This defines a Root Guru, but you can learn from many teachers. The Guru-disciple relationship is very important in Vajrayana. The commitment towards a Guru on the part of a disciple needs to be sincere and may not be broken. It can be very difficult and confusing to uphold commitments with many teachers.

Question: Unfortunately, only a few of us have the opportunity to see and speak with our teacher very often. If we're lucky, we get an interview when we do see him once every few years. We can't call our teacher on the phone when we have questions. We just don't experience our teacher often enough, even if we are very devoted.

Rinpoche: That is very true. Many students do not have the opportunity to spend much time with their teacher. Actually, the situation in the West is much better than it was in Tibet. The Lamas return regularly and you have the chance to see them often, therefore I see no hindrance. A beginner needs to hear the teachings from a qualified teacher, but progression along the spiritual path does not depend upon being with a Lama for a long period of time. The methods that are taught for practice suffice, and let us not forget that everything depends upon one's karma. A student needs to be open, have confidence and sincere dedication. If a student is open, then there is no distance between a Guru and a student. Je Gampopa, for instance, did not spend much time together with his Guru, Jetsün Milarepa.

Question: At which exact point is it possible to engage in Vajrayna practice? And what is the bond to the teacher?

Rinpoche: A disciple enters Vajrayana when he or she receives an initiation and then begins engaging in the practices of Ngöndro.

Concerning your second question, there are 14 Vajrayana vows. The essential point is the Guru-disciple bond; a student sees the Lama as a Buddha and has unshakeable confidence. The Guru takes the responsibility upon himself to lead pupils to enlightenment. If you receive initiations from other Lamas, you need to respect and see them as pure, but a student doesn't have the same connection to all Lamas. Openness towards a specific teacher is natural and not contrived.

Question: A realized individual is free of karma and concepts. Do thoughts then arise according to certain laws and rules? Is there a structure to the thinking of an enlightened being? Where does it come from – otherwise everything would fall apart? Or do thoughts just accord with the needs of beings? Does an enlightened Buddha just give instructions to unenlightened people?

Rinpoche: I did mention that Buddhahood means realization of primordial wisdom that possesses two aspects: realization of emptiness and all-knowing, i.e., omniscience. Realization of emptiness does not bring on a blank state of mind, rather it is the state in which mind's clarity unimpededly manifests. Usual hopes and fears have nothing to do with omniscience.

Student: I understand, but that wasn't my question.

Rinpoche: Let me finish. Realization of Mahamudra means that no obscurations conceal the true nature after a student has passed beyond the four stages of practice, which are one-pointedness, freedom from mental contrivances, one-taste, and no-more meditation. One's obscurations diminish and gradually cease while one engages in these practices. While meditating these stages of practice, a disciple realizes his or her own mind's true nature ever more clearly and clinging to things diminishes and eventually ceases. When the result of Mahamudra has been realized, then omniscient wisdom manifests spontaneously and an advanced practitioner has been able to integrate it in life fully, not only during formal meditation sessions. Omniscience is a changeless, continuous state.

Student: I understand the difference between appearances and our thoughts about them. A person who has realized Mahamudra is not attached to thoughts and does not develop further thoughts by following after them, but it still happens. It is taught that we experience appearances in accordance with our obscurations. A realized being has no obscurations. In which way do appearances then occur? Where do they come from when there are no more obscurations?

Rinpoche: It is true that Buddhas do not experience phenomena due to karma, because they have no karma. Appearances arise out of emptiness, which doesn't mean they disappear for an enlightened being. Phenomena are empty of inherent existence; they lack self-substantiality and therefore appear in dependence upon causes and conditions. This never changes, not even when someone is enlightened. Lord Buddha offered 84,000 teachings, emanated as Kalachakra and presented "The Kalachakra Tantra," emanated as Hevajra and presented "The Hevajra Tantra," taught "The Samadhiraj Sutra," and so much more. Disciples received these instructions while they themselves were in the realm of relative reality. Ultimately, Lord Buddha never taught; his teachings are evidence of a Buddha's unfathomable activities. We think that the Buddhas teach, but actually they don't.

Question: Are special insight and Mahamudra practices the same?

Rinpoche: They are one; there are just different terms. Shamata and lhagtong are practiced by the Shravakas, Pratyekas, and disciples of Mahamudra.

Question: I think of the many kalpas and that many beings have become Buddhas. Dharmadhatu encompasses all kalpas. Are all one Buddha in the end ? There should be more and more Buddhas and increasing Buddha activity.

Rinpoche: It is true that many great beings achieved Buddhahood. As to Dharmadhatu, this question does not arise to a Buddha.

Student: We learn that Buddha Amitabha made special prayers and therefore there is Devachen. This brought up the question in my mind.

Rinpoche: Devachen is a pure realm. Devoted practitioners can be born in Devachen and quickly attain realization without hindrances. In truth, Buddha activity is not separate from living beings, rather living beings are separate from Buddha, and that is why various Buddhas appear. Buddha Amitabha is the same as all other Buddhas. Now, there are various aspects of the pure Buddha fields and they depend upon the connection a practitioner has. Buddha activity, though, is non-differentiate.

Question: I have a similar question. It is often said that a specific Bodhisattva will stay in samsara until every single living being is liberated from suffering. Somehow that doesn't seem possible, because there are no more other suffering beings when you are liberated.

Rinpoche: There aren't?

Student: Well, you can't liberate all beings if you aren't attached to appearances. Samsara continues for those in samsara. Somehow it doesn't make sense.

Rinpoche: Yes, I understand what you are saying. Bodhisattvas make such a strong commitment not to become enlightened themselves until all beings are liberated. This commitment empowers and enables them to become liberated very fast. Once they become a Buddha, they can help even more living beings without effort. You said that they aren't concerned about others because they are liberated. This is not so, because their concern and activities of body, speech, and mind are spontaneous, spontaneity being a quality of Buddhahood.

Student: That's clear. What you say sounds educational. It's wrong to say "until samsara empties," because there isn't such a thing.

Rinpoche: I think that there is an end, because all beings have the Buddha nature.

Question: Is there perception of an existing world or does it dissolve when the mind abides in itself? Do we then perceive an individual?

Rinpoche: It depends upon practice. In the beginning, one thinks that mind rests in itself, that there is somebody meditating. Such concepts diminish gradually and a practitioner reaches a stage that is totally free of mental contrivances.

Question: When Buddhahood is achieved, does such a realized individual naturally benefit a limitless amount of beings or does benefit depend upon the wishing prayers he or she made while on the path?

Rinpoche: Perfect Buddhahood and Buddha activity are always the same. Benefit depends upon prayers while a practitioner is traversing the Bodhisattva levels to Buddhahood.

Question: What is the meaning of singing the dohas?

Rinpoche: In general, there is no significance to melodies. Jetsün Milarepa taught and sang a specific melody, so it is a wonderful inspiration to sing these songs during practice because he did so. The transmission becomes more powerful.

Question: Are the pure realms created by our mind or do they exist by themselves? Are they located in a place we can reach or are they created during life? Can our mind go there if we choose? Is Devachen only a vision of our mind or does it exist on its own?

Rinpoche: Devachen is a pure realm and is not created, not really. You just have to wait – yes.

Question: Rinpoche, you said that melodies in general are not so important, but the melody of Milarepa's songs can inspire us. We don't know the tune. Would you sing it for us?

Rinpoche: Can you help me? Okay, I'll sing, but I'm not sure about the particular melody for "The Conversion." There is a melody used in the Kagyu Tradition for the songs in "The Rain of Wisdom" (translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee under the direction of Chögyam Trungpa, Shamhala Publications, Boston & London, 1980) so I will sing, but please do not applaud afterwards. Thank you very much.

>

"In general, at a precise moment in time, when disciples merit and the Lama's compassion connect with each other, the great and genuine beings will give up one emanation body and appear in another. Once again, disciples will be able to meet face to face with the supreme emanations and to truly enjoy their portion of the nectar of their Lama's speech." Venerable Thrangu Rinpoche, Foreword to "EMA HO! The Reincarnation of the Third Jamgon Kongtrul," published by Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang, Pullahari Monastery, Nepal, 1998.

Dedication

May the life of the Glorious Lama remain steadfast and firm.

May peace and happiness fully arise for beings

as limitless (in number) as space (is vast in its extent).

Having accumulated merit and purified negativities,

may I and all living beings without exception

swiftly establish the levels and grounds of Buddhahood.

The teachings that His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche the Third generously offered were presented at the Kamalashila Institute in Germany in 1989. Photo of Jamgon Lama the Fourth courtesy of Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang. Translated into English, transcribed, and edited by Gaby Hollmann (1991/2007, responsible for any mistakes). Copyright Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang, Pullahari, Nepal, 2008. May virtue increase!