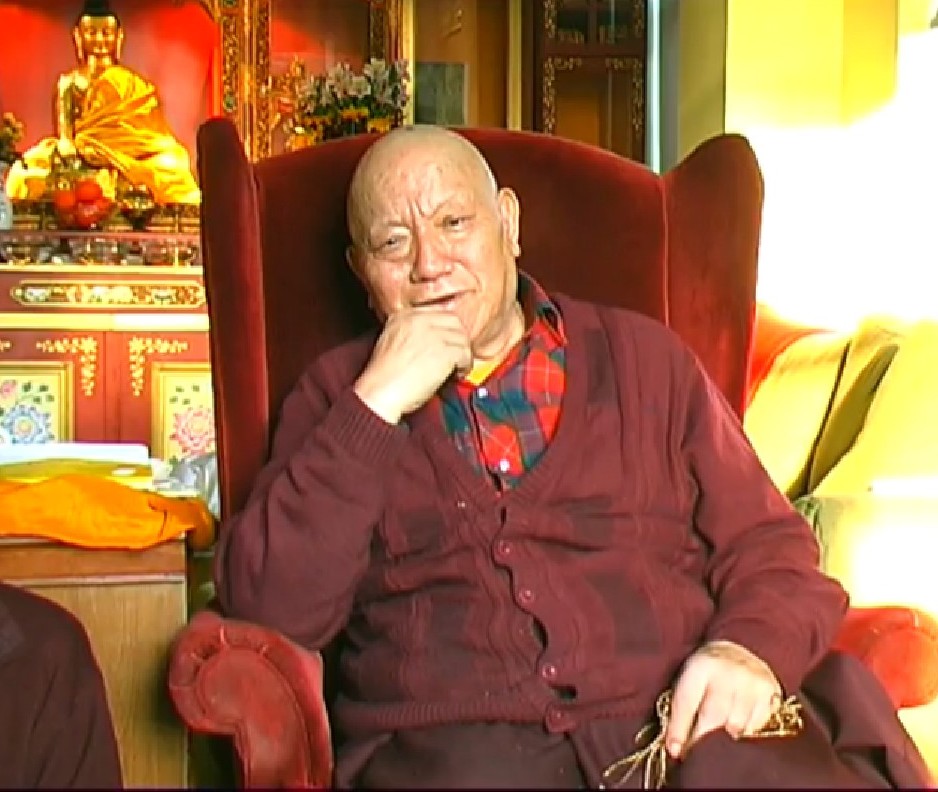

Chöje Lama Namse Rinpoche

Gaining Unobscured Certainty of Dharma

by Accumulating Merit and Wisdom

Let me speak about the six perfections in the context of merit and wisdom that a Mahayana disciple needs to accumulate while gradually gaining unobscured certainty of the Dharma. There are three ways to practice generosity, the first paramita: There is generosity of giving material help, generosity of helping living beings be free from fear, and generosity of giving the Dharma teachings.

Generosity means having the pure motivation and then giving whatever one can to those who have less, who are in need, or who have nothing at all to survive on. It is so easy to share what one has, whether daily goods or time. Working for welfare centres, youth organizations, old-age homes, or hospices is also a very positive way of being generous. This doesn't mean to say that a practitioner should give everything he or she has away or spend every minute of the day with needy people, which would be quite meritorious if and only if the motivation to make others happy and enable them to lead a meaningful life is altruistic. There is not much merit if someone who is very rich and hoards possessions offers a little to those who are hungry and helpless. There is much merit, though, if someone who is poor helps those living in even more scarcity. The accumulation of merit does not depend upon the amount one offers, rather upon one's motivation.

If one wishes to practice the first paramita of generosity and perfect the accumulation of merit for one's own benefit as well as for that of others, then the best thing one can do is become free of ego-fixation and have no expectations when one is generous. Of course, it's not possible to be totally free of self-cherishing, and there is nothing wrong with being happy when one was able to help or be of service to others. The point is that one's merit increases the less one thinks of oneself.

Giving others freedom from fear is a special way of being generous. There are many people in our immediate environment who have problems, worry about sickness or loss, or are afraid of someone or something. Giving freedom from fear means helping those who experience difficulties by listening to them, by offering advice, or by giving them shelter from natural catastrophes or a safe place to live if they are being chased by unlawful persecutors, bandits, or animals of prey. The best way to help those seeking freedom from fear is inviting them to take refuge in the Three Jewels. Of course, one may not force anybody, but offering persons who are not directly being threatened and are not trembling with fear the opportunity to take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha is truly an exceptional way of giving. And offering Dharma instructions that one has learned and practiced very well and answering questions adequately is the very best way of perfecting generosity. But I do want to stress and warn you that giving the Dharma teachings to others as long as you still have doubts in your mind is not correct at all.

Discipline is the second paramita that a sincere follower of the Great Vehicle practices. It refers to ethical behaviour that accords with specific rules and regulations that are set up for one's own benefit and for the sake of others. There are various methods in Buddhism that help practitioners remember ethical behaviour - taking full ordination, partial ordination, or lay-practitioners' vows. It is possible to take only a few of the five lay-followers' vows, which are not to kill, steal, lie, etc. Vows are supports that help practitioners abandon unvirtuous actions and cultivate virtue. If we respect and keep the vows we have taken, then it is very good for us and others, too. It is important to recall again and again that any practice one does is carried out for one's own benefit as well as for that of all living beings. In Secret Mantrayana, it is a custom to request initiations from a Lineage-Holder or qualified Lama so that one is empowered to engage in specific meditation practices. Vows are taken in connection with each empowerment, and these vows may not be broken, either. The most excellent kind of discipline that one can have is always striving to benefit living beings without any selfish intentions.

The next unsurpassable perfection is patience. It can be practiced on many levels and on many occasions. One can be patient with oneself on a larger scale, too. In any case, it is best to practice patience when very difficult situations arise. It is important to practice patience by not retaliating, by not hitting back, by not getting angry when one is being blamed for something one did not do. Practicing patience when things seem to go wrong is very good for oneself and others. Patience even has the power to stop wars from starting in the first place and to guarantee peace.

The purpose of the first three paramitas is to accumulate merit; that of the last two of the six is to accumulate wisdom. The fourth unsurpassable perfection, joyful endeavour, is the bridge that connects the accumulation of merit with the accumulation of wisdom and pertains to all paramitas. If it is missing, then one will hardly accumulate merit and wisdom. On a worldly level, one won't make it through school or be successful in one's job without it. Endeavour - all the more so joyful endeavour - is important if one wants to accomplish a goal. If one wants to be generous, disciplined, and patient, one must be diligent. If one wants to practice meditative concentration and have wisdom-awareness, i.e., discriminating awareness, then one needs to be diligent. Any projects carried out without it will not work, so it is necessary to develop and increase one's joyful endeavour.

There are two kinds of meditative concentration, worldly and transcendent. Tranquillity meditation is worldly meditative concentration that leads to a higher birth in the cycle of existence. There are also concentration practices that lead to freedom from birth in samsara, which is enlightenment.

Turning our attention to discriminating awareness now, there are two types: mundane and transcendent. Mundane intelligence is knowledge of the arts, sciences, crafts, etc. one needs to know in every job and in order to live satisfactorily. It is important to have mundane intelligence, but it won't help anyone leave the misery and woe experienced in samsara behind. Only transcendent wisdom-awareness will lead to freedom from samsara and to attainment of perfect awakening, which is buddhahood. It is important to acquire both types of awareness, though. It is needless to say that transcendent awareness exceeds all worldly knowledge that one can collect.

There are three kinds of transcendent wisdom-awareness: wisdom that arises from hearing and receiving the Dharma teachings, wisdom that arises from reflecting the teachings that one has received, and wisdom that arises from meditating them. Wisdom-awareness that arises from hearing and receiving the instructions is won by listening to teachings that qualified Lamas impart or reading books that explain the Dharma. What topics are dealt with in Dharma teachings and books? Instructions on meaningful and meaningless karmic cause and effect, on distinguishing the virtue and vice of cyclic existence, on abandoning sin and unvirtuous actions, on purifying mental obscurations, on cultivating faith and devotion in the Dharma, and so forth. The Third Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje wrote in The Mahamudra Prayer: 'Appearances that never existed are eluded as objects. Overwhelmed by ignorance, the one who apprehends is reified as the subject. Swayed by clinging to duality, we wander in the expanse of cyclic existence. May the root of ignorance and confusion be dissevered with wisdom. '

Having received instructions, it is necessary to reflect them critically and thoroughly so that one's understanding and knowledge of Dharma become firm. Having won an intellectual understanding, it is then necessary to meditate the teachings that one has understood well so that one experiences them for oneself and gains certainty. Without knowledge that distinguishes all phenomena, it is impossible to gain certainty in the teachings one heard and reflected. Then everything one knows remains intellectual and is of no use when one dies. Therefore, it is very important to meditate the teachings that one has received and discerned so that unobscured certainty is born in one's mind.

The certainty one gains by meditating the Dharma is realization of mind's true nature. If a diligent practitioner has gained certainty of mind's true nature, then he or she is not swayed by any conditions whatsoever. If one experiences this for oneself, then one is steadfast.

In summary, there are the perfections that disciples practice. The first three are practiced in order to accumulate merit and the last two are practiced in order to accumulate wisdom-awareness. The fourth perfection is the link between the two types of accumulation. It is impossible to accumulate merit and wisdom without joyful endeavour.

I want to urge you to practice the six unsurpassable perfections, but I want to warn you that you should not over-estimate yourself and think it is as easily done as said. Western practitioners are not meditating in caves high on a mountaintop and engaging in the Dharma in total seclusion. If you over-estimate yourself, all your endeavour will be in vain, because pride arises and increases as a result. Please be careful there, be honest with yourself, and always check your abilities and shortcomings.

The paramitas are not meant to be practiced in the order in which they are listed. Even though the first three are closely connected and follow one after the other, every paramita can be practiced when situations call for them. Actually, there are ten paramitas; the last four are more subtle practices of the first six. They are relevant for very advanced practitioners who have attained Bodhisattva levels of realization. Thank you very much.

Dedication:

May the life of the Glorious Lama remain steadfast and firm.

May peace and happiness fully arise for beings as limitless (in number) as space (is vast in its extent).

Having accumulated merit and purified negativities, may I and all living beings without exception swiftly establish the levels and grounds of Buddhahood.

Presented at Theksum Tashi Choling in Hamburg, July 2007. In reliance on the German rendering kindly offered by Thomas Roth, translated into English and edited by Gaby Hollmann, with sincere gratitude to Madhavi Simoneit, Ani Dorothea Nett, and Hans Billing, our kind webmaster. May virtue increase!